About ECV

| What We Do |

|

Vision and Mission

|

|

Programs

| |

|

| Who's Involved |

|

Board of Trustees

|

|

Program Staff

|

|

Partnerships

| |

|

| Who We Serve |

|

The Children of Eggerts Crossing Village

|

|

Other Lawrence Township Children

| |

|

| ECV History |

|

2020-2021 Academic Year Challenges and Solutions

|

|

A Brief History of ECV

| |

|

|

2020-2021 Academic Year Challenges and Solutions

Chelsea Ezzo

Educational Testing Service

The 2020-2021 academic year was a challenging time in K-12 education, both in Lawrence Township, NJ, and across the United States, and these challenges were exceptionally steep for underserved students. The COVID-19 pandemic rendered in-person instruction unsafe, leaving school districts with limited options for delivering instruction. Many, including the Lawrence Township Public Schools (LTPS), began the school year with virtual classrooms via an online meeting platform such as Zoom. This format presented a wide variety of challenges, both technological and pedagogical. Foremost among them was the need to adapt student engagement strategies to a virtual setting. In January of 2021, LTPS switched to a hybrid model whereby different students had different schedules that combined in person and virtual instruction. Although in person instruction provided more and better opportunities for teachers to foster student engagement, this model still left parents with a non-standard schedule (or set of schedules) to juggle among other pressing priorities. Families in underserved communities were particularly ill-equipped to respond to disruptions to their children’s education, with less consistent internet access, higher likelihood of employment as essential workers, and higher rates of occupational exposure to COVID-19 (Aguilera & Nightengale-Lee, 2020; Catalano et al., 2021; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2021; Yaya et al., 2020). Within LTPS, there was a demonstrated need for additional support to navigate the fluctuating education landscape. Throughout the 2020-2021 academic year, the unique partnership between LTPS and Every Child Valued (ECV), a set of community-based, out-of-school programs in Eggerts Crossing Village, an affordable housing development in Lawrence Township, created the opportunity to assist such families in the LTPS district with the challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though the focus of this report is on the work that was generated by the LTPS partnership with ECV, it’s useful to describe the backdrop against which this partnership occurred, including the multi-faceted LTPS response to the challenges wrought by the pandemic. When instruction was exclusively virtual, some students were not able to participate in live instruction because they had to accompany a parent to work or because there was an insufficient number of devices in the home to accommodate each child. To address this concern, lessons were recorded so that families were more easily able to manage work schedule, device, and other constraints. Students still were required to complete the assigned work, but they had more flexibility in when and where they received instruction. In terms of device distribution, because one device per family was insufficient, LTPS provided multiple devices to families that expressed the need. Families kept these devices through the 2020-2021 school year. In addition, LTPS provided internet accessibility to any family that expressed the need, distributing more than 100 hotspots in the first two months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Social and emotional health also was supported, with daily lessons for students and weekly sessions with staff.

The switch to a hybrid model involved several different schedule offerings dependent on individual student needs. Some special education students attended in person each morning. Other students attended in person two mornings per week and then joined their classrooms virtually from home on the other days. Students who continued to engage in learning on an exclusively remote basis received additional instruction from a teacher in the afternoon. Regardless of the frequency, the addition of teachers’ physical presence was a vast improvement in their ability to deliver quality instruction. Yet, because all hybrid options entailed, at most, half days of in person instruction, all students continued to receive virtual instruction for a substantial portion of their day. LTPS efforts were by no means unique in this regard; districts around the country employed similar instructional configurations in response to unprecedented, pandemic-induced constraints.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic disruption to K-12 schooling is challenging to estimate for many reasons. Many states suspended standardized testing during the spring of 2020, and some suspended it into the 2020-2021 school year. Those students who did test in spring 2020 did so under conditions that varied greatly from one another and from previous testing administrations, so the degree to which comparisons of their results can be made across time is unclear. And, while standardized test scores are valid indicators of academic progress, they do not capture the full picture. Social-emotional learning (SEL) factors, such as growth mindset, social awareness, self-efficacy, and self-management, also predict individual student achievement (Kanopka et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the national data that do exist indicate that the interruptions of the pandemic resulted in substantial academic gaps across grades and subjects, as evidenced by standardized test score declines (Kuhfeld et al., 2022), and that the impact is larger for underrepresented and lower income students (Halloran et al., 2021; Lewis et al., 2021). Preliminary research estimates suggest that pandemic-related interruptions to learning will impact SEL outcomes as well (Santibañez & Guarino, 2021).While these data are not indicative of the results from LTPS, they nevertheless underscore concerns about underserved student academic achievement and social-emotional learning to which the LTPS and ECV partnership is responsive.

Nested within the heart of LTPS is ECV, a set of community-based, out-of-school programs designed to supplement and support student educational progress, particularly for low-income LTPS families. The programs have a strong reputation in the community they serve. They also benefit from a close and collaborative relationship with LTPS to whom they provide annual reports of student progress and have regularly scheduled partnership meetings throughout the school year. To this end, ECV typically conducts independent academic testing of their enrollees at the beginning and end of the school year; however, this was not possible between March 2020 and June 2021 due to staffing constraints, limited windows for in-person staff/student interaction, and the need to prioritize student learning activities. Lack of traditional data sources created for ECV a challenge experienced by many other educational entities during this timeframe -- they engaged in substantial efforts to sustain academic and SEL-related programming, yet they had no way of formally evaluating the impact of their actions. This report documents one solution to that challenge. An evaluator conducted a series of qualitative interviews with ECV academic enrichment coaches and with parents of students who participated in ECV programs during the 2020-2021 school year. Findings from those interviews describe in detail the challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic presented to ECV management and staff, the solutions they implemented in response, and stakeholder perceptions of the impact of those solutions on students’ academic and SEL progress.

Program Description

ECV is a set of neighborhood-based, educational enrichment programs located in Eggerts Crossing Village in Lawrence Township, NJ. Programs are available for students in grades K-12 and include the Breakfast Program (BP), the After School Program (ASP), the Summer Academic Enrichment Program, and the Tutoring Program, as follows.

-

The BP, available to K-12 student residents of Eggerts Crossing Village, operates from 6:30 a.m. – 8:30 a.m., Monday thru Friday, during the school year. Students receive a bagged breakfast, homework assistance, and an escort to the school bus.

-

The ASP, available to K-6 student residents of Lawrence Township, operates from 2:45 p.m. – 5:30 p.m., Monday thru Friday, during the school year. Students receive math and ELA academic enrichment and homework assistance and engage in a wide variety of extracurricular clubs and activities. The ASP has two locations, one for K-3 grade students, and one for 4-6 grade students.

-

The Summer Academic Enrichment Program, available to K-6 student residents of Lawrence Township, operates from 8 a.m. – 4 p.m., Monday thru Friday, for six weeks in the summer. Students receive math and ELA academic enrichment and engage in academic and extracurricular activities related to a theme of the week, culminating in a weekly field trip.

-

The Tutoring Program, available to Eggerts Crossing Village student residents in grades 7-12 and those who aged-out of the After School Program, operates from 6 p.m. – 8p.m., two evenings a week during the school year.

All of the programs aim to build a continuous developmental and educational experience for low-income Lawrence Township children.

Method and Sample

Two ECV Destinations Coaches were interviewed about their experiences during the 2020-2021 school year with three ECV programs (the BP, the ASP, and the Summer Academic Enrichment Program). Both Destination Coaches are employed by LTPS as teachers in the school(s) and in the ECV ASP and through this partnership serve as a liaison between ECV and LTPS. In this dual role, they sometimes instruct the same students in both locations. Combined, they instructed 100% of the students in the ASP in that academic year. The Destination Coaches responded to a series of questions about what it was like to teach in the different ECV programs and about their perceptions of how the programs impacted student attendance and engagement in school.

Three parents/guardians, representing 10% of the families enrolled in any ECV program that year, also were interviewed regarding their family’s experiences with the BP and ASP during the 2020-2021 school year. Collectively they had seven children enrolled in either the BP or ASP. Parents responded to a similar set of questions about what it was like to engage with the various programs and about their perceptions of how the programs impacted their children’s attendance and engagement in school.

Results

Coach and parent insights across the three programs are reported below according to the following four major themes: 1) Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2) ECV Program Strengths, 3) Close Collaboration with LTPS, and 4) Hopes for the Future.

The first major theme, Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic, is discussed in terms of student Attendance and Engagement challenges and the corresponding solutions that ECV management, coaches, and staff implemented to mitigate their impact. Several ECV Program Strengths were identified as part of the second major theme. Programming Flexibility addressed the wide variety of adaptations made by ECV management and staff to ensure continuous operation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The discussion on Strong Family Connections describes the close and supportive relationships between ECV coaches and staff and the families located in Eggerts Crossing Village. The Remarkable Student/Teacher Ratio is discussed in terms of its impact on student academic engagement. The description of the Built-in SEL Component touches on the multi-dimensional personal care extended to students in order to help them develop healthy personal and academic identities, communicate confidently, and maintain supportive relationships. Finally, Close Physical Proximity to Student Homes is a key component of the ECV model which yielded unique benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major Theme #1: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Coaches and parents described a wide range of factors that impacted student attendance. In some cases, the adults in the home lost their jobs, resulting in low motivation for everyone to wake up in the morning and no structure for the day. In other cases, students were in homes with one parent who worked overnight and who was asleep during the time students would normally awake to get ready for the day. These students weren’t required by their families to wake up early for school. In many cases, parents were essential workers experiencing the stress of long and/or inconsistent working hours, frequent schedule interruptions due to COVID-19 exposures and subsequent quarantine mandates, job loss, economic insecurity, difficulty keeping up with internet bills, health concerns, and mental health strain. Several students had COVID-19 in their homes, and, in some cases, family members were lost. Others had parents who traveled out of state, thus rendering their child ineligible to attend school or ECV programs for two weeks (the state mandated quarantine period). In instances where such travel was a regular occurrence, a long-term pattern of intermittent attendance was created. The coaches indicated that the combination of a hybrid schedule plus multiple quarantines resulted in their LTPS students’ decreased motivation for academic engagement and achievement.

A final, systemic cause of decreased attendance was that of uneven access to technology. The absence of a 1:1 device-to-student ratio as well as the lack of a consistent, at-home Wi-Fi connection were the primary examples of this phenomenon. Fortunately, these factors were mitigated to some extent by LTPS. Still others experienced a range of day-to-day technical struggles including challenges related to logging in and resetting passwords and issues with keeping multiple student laptops charged simultaneously.

In all these situations, the numerous, extended, and intensive challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic placed school attendance and engagement at a lower priority relative to day-to-day coping. Impacted students missed substantial portions of online instruction and/or missed the bus, and therefore had fewer opportunities for in-person learning.

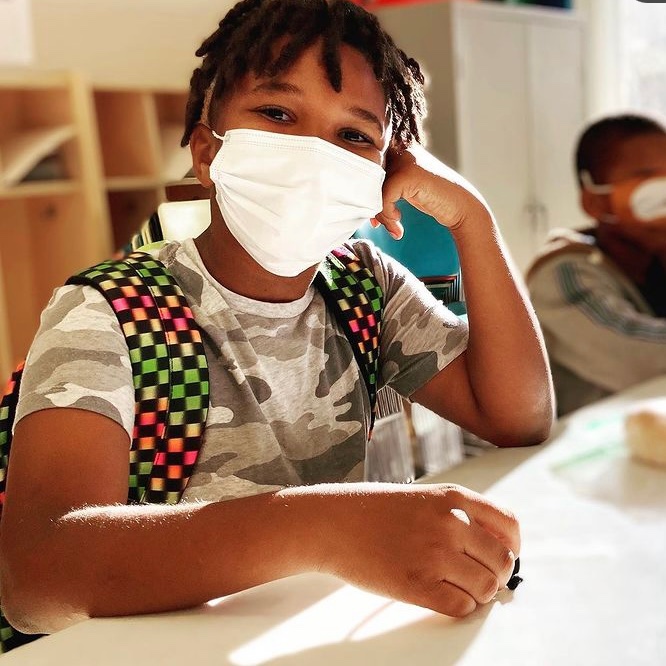

A significant challenge to learning brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic was decreased student engagement to participate in online learning generally. Fewer extrinsic incentives resulted in reduced motivation to attend or engage with academics, whether online or in person. The coaches indicated that the limitations inherent to the virtual instruction format left them without immediate options for recourse when students turned off their cameras or otherwise disengaged from instruction. As the school year progressed, the two coaches that were interviewed reported waning attention spans for their online, LTPS classroom instruction across the board. Once hybrid attendance was an option, their students who had to return temporarily to online learning as part of a quarantine viewed the situation as a punishment. As one coach observed, “they were checking out immediately.” The interviewed parents also indicated that students were bored, sometimes sleeping, in their online classes, believing that the lack of a physical connection left them without motivation to stay involved with their classes. In all of these instances, challenges to student engagement were exacerbated by the difficulty classroom teachers experienced in identifying stimulating asynchronous activities.

An additional barrier to engagement in remote instruction was students’ home environments. One coach described the experience as “really chaotic” when multiple students in the same family were trying to do online learning in the same room, an experience which was not uncommon. In some cases, students were responsible for younger siblings, sometimes even holding them on their laps and entertaining them while they were on camera for their own class. Parents also described distracting home settings resulting from multiple individuals’ activities occurring simultaneously in a small space, saying that it was “very difficult to create an environment where [students] could concentrate and maintain a routine.”

Even in instances where an individual home setting was quiet, the fact that students in the remote classroom would sometimes talk over each other and visibly or audibly stray off task created a challenge for those attempting to pay attention. One mother stated that her son became so frustrated that, for a particularly challenging stretch of time, he stopped wanting to connect to other people generally. “He would move his camera so his face couldn’t be seen. He would make excuses about the high-speed connection … those were some dark days.”

Another substantive hurdle to student engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic was the frequency with which students were hampered by difficulties in demonstrating their knowledge within the constraints of an online environment. As one coach described it, “showing what you know on the computer is not easy, and it’s not always authentic.” This situation was particularly problematic for younger students for whom response mechanisms were not sufficiently user friendly or who were not able to work out an answer entirely on the computer.

As ECV staff became aware of individual family circumstances, they created attendance plans to help students attend school, whether online or in person. They complemented LTPS engagement efforts by reaching out to families by text, phone, email, and in-person when students were absent. In response to some of the technical challenges, LTPS provided laptops to students who needed them. They also provided Wi-Fi hubs that could be installed directly in students’ homes. ECV staff aided in this initiative by providing ongoing, in-home, technical support and troubleshooting to those who needed it.

The most substantial ECV solution to attendance and engagement challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is discussed in more detail in the following section, was to create a Learning Pod whereby students could gather together daily to eat a meal, receive assistance logging in to their classrooms, and engage in online learning where they could focus without distraction. This supportive, in-person environment helped to increase student attendance motivation, though the coaches and parents observed that it did not completely restore it to previous levels for their students. Student engagement was fostered by increased face-to-face adult engagement. Using both passive (daily presence in a learning environment) and active (homework reminders and course setting, technical support, socioemotional encouragement and validation) approaches, ECV coaches and staff created consistent mechanisms for student accountability that supplemented those instated by LTPS.

It is important to note that this innovation was not without its own challenges. During the transition to the Learning Pod model, there was a shortage of ECV staff to assist students in logging in to their classes (the Learning Pod model was originally staffed by those running the BP, which has higher staff to student ratios than the ASP). This created a resource strain until more staff could be hired to decrease the ratio.

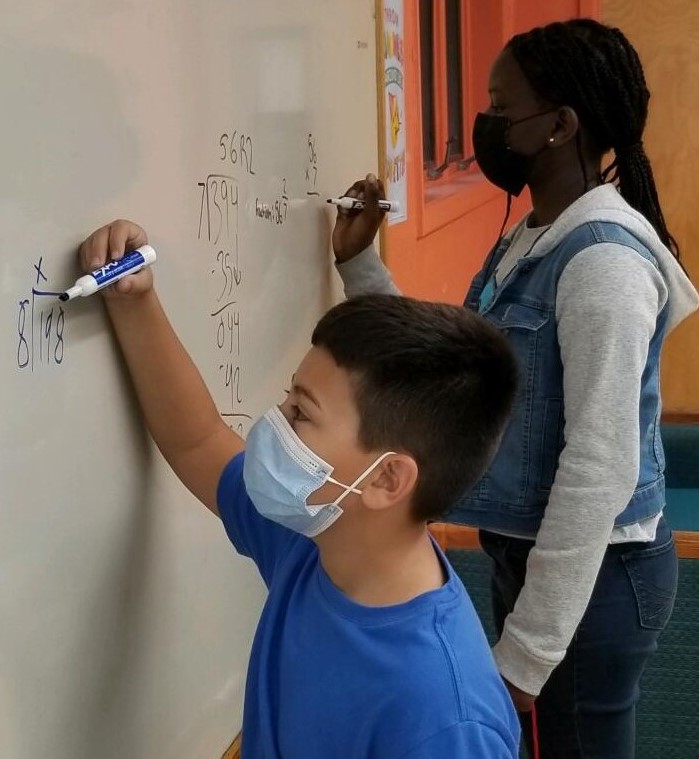

Key components of the ECV Learning Pod model were developed specifically to alleviate student challenges with online learning. Students who found it difficult to complete and submit their work via an online platform were given additional, hands-on assistance. In some cases, the student only needed a couple of demonstrations in providing a response (e.g., clicking and dragging) before they were able to replicate the action independently. However, some students needed help in working out an answer on paper as well as with entering it into the computer. In other situations, students would verbally communicate to staff their responses to online questions or prompts, and the staff would enter them on their behalf. Staff helped some very young students take pictures of their work, which the staff then sent to the students’ classroom teachers. In all instances, ECV coaches and staff helped provide creative alternatives for students to maintain accountability and demonstrate their engagement while preserving the integrity of their work (i.e., by not doing it for them).

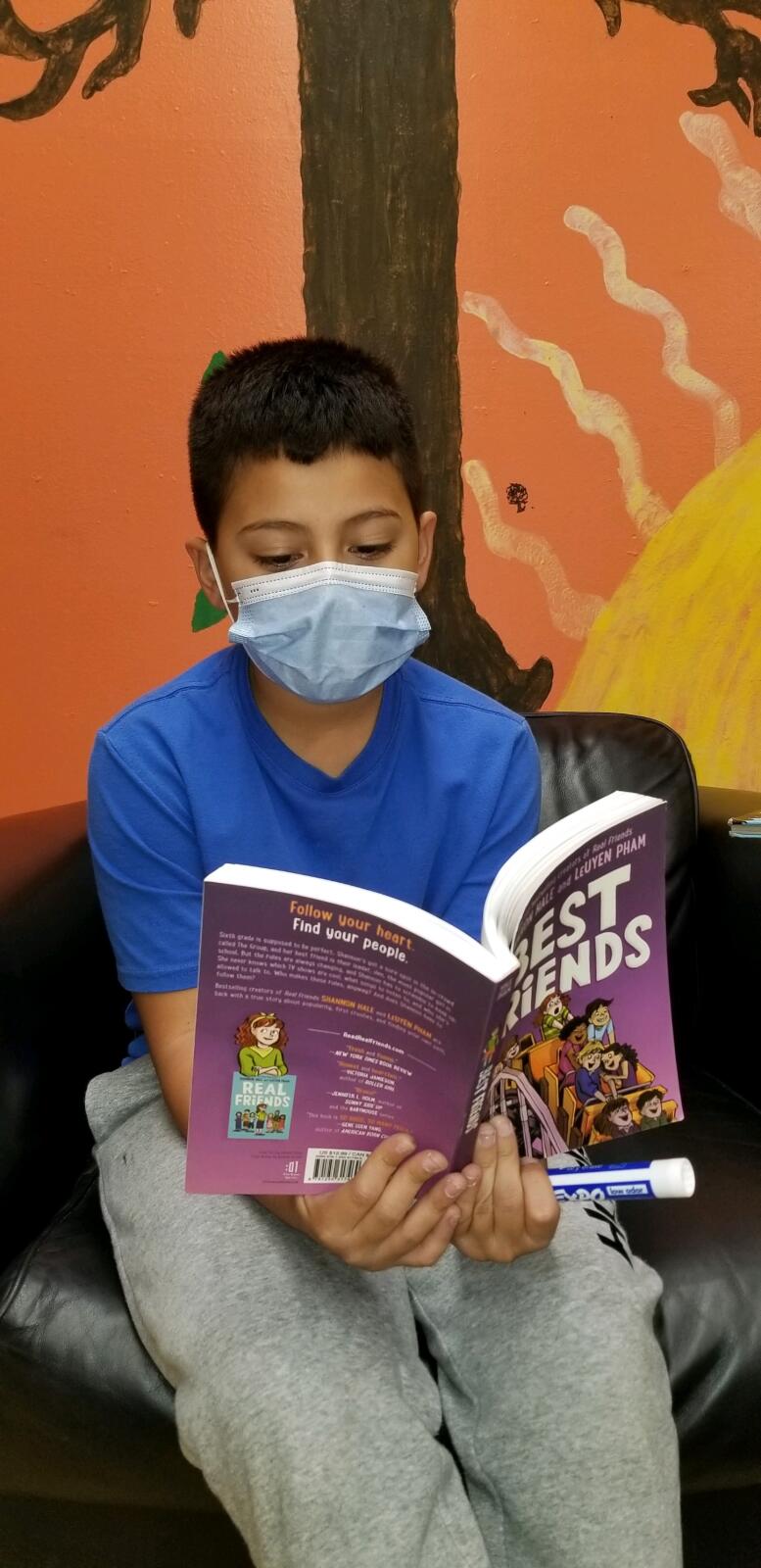

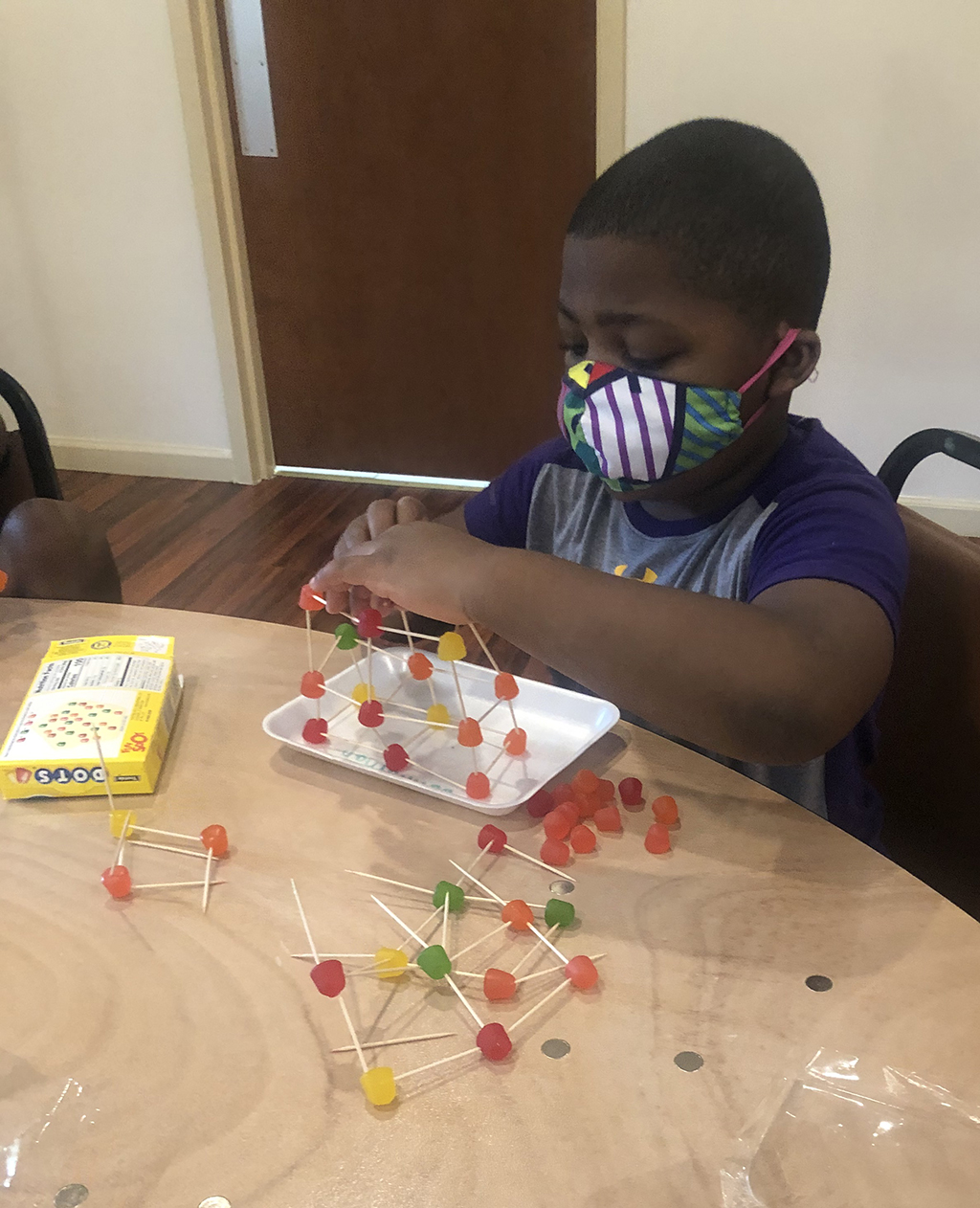

ECV coaches and staff additionally noted that students often appeared overwhelmed and tired from the amount of daily screen time. While the primary focus of the ASP was to help students complete their assignments, ECV designed a set of interest clubs to complement online learning. These small groups were organized around topics such as sports, drama, and science and provided a fun and hands-on means for students to continue to engage academic concepts – and decompress from screens – within the context of their hobbies and interests.

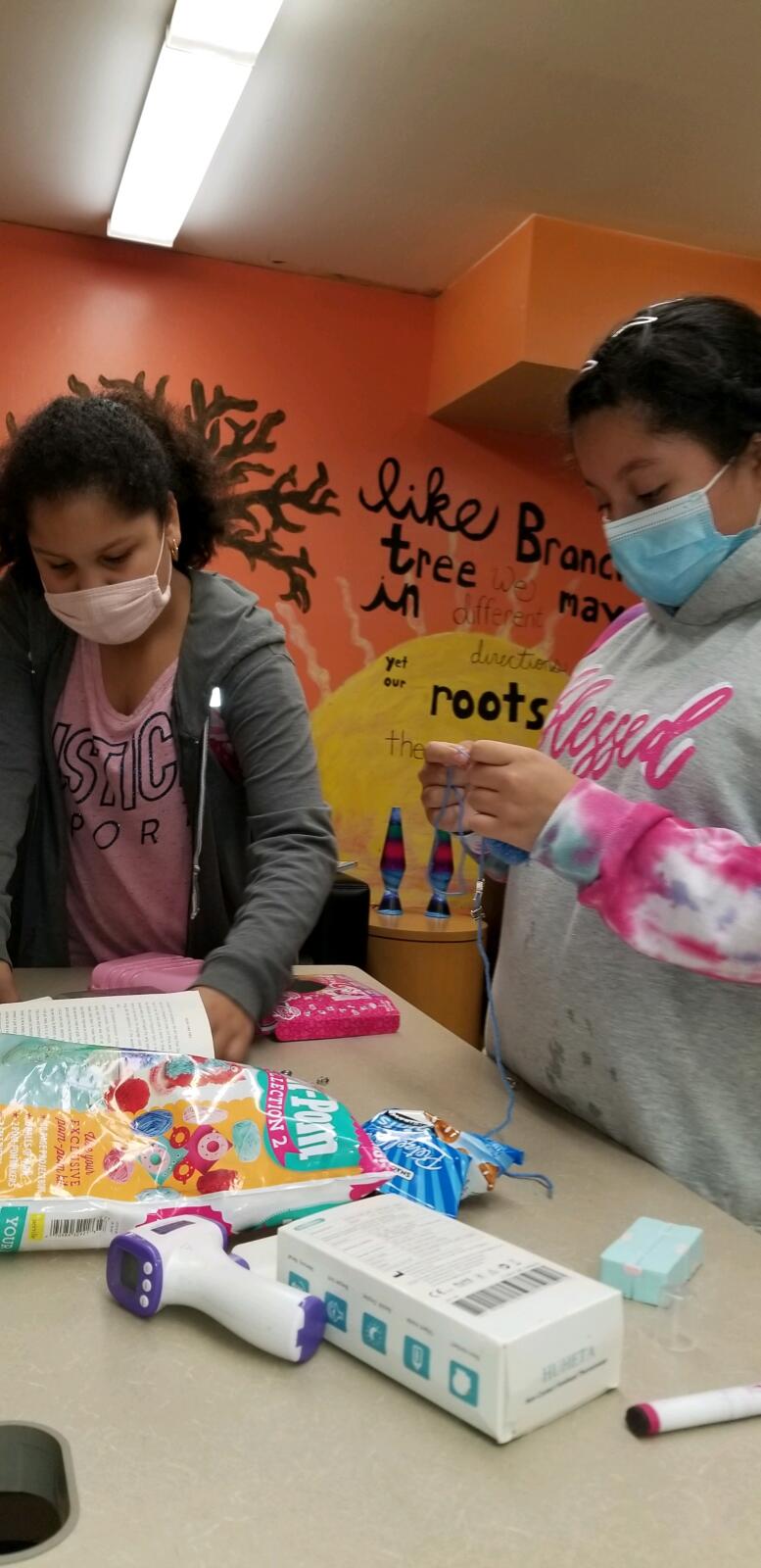

Major Theme #2: ECV Program Strengths

Coaches and parents praised the adaptability demonstrated by program leadership in finding ways to safely provide academic, logistic, and SEL support despite the many pivots in schedule and format necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Students were not always consistent in their understanding of and engagement with changes in the school schedule, so ECV staff regularly served as a communication bridge by conducting masked, socially-distanced visits to students’ homes to provide updates, to share information about ECV programming and service options, and to reiterate norms and expectations regarding school participation. Staff also asked about families’ wellbeing and needs, creating opportunities for sharing and eliciting avenues for further support.

Most significantly, ECV created a Learning Pod, making it possible for students to safely access the K-3 site so that they could receive in-person computer technical and navigational support to log in to their online school classroom. This adaptation was provided in accordance with school scheduling and was particularly important for students in grades K-3 who benefitted from additional guidance in this area. When school was completely remote, students were able to come to the K-3 site in the morning to eat breakfast together, log in to their classrooms, and begin their day with ECV BP staff support. When LTPS implemented a hybrid schedule where students attended school in the morning and returned home at 12:30 p.m., ECV had dedicated staff to support student login at the K-3 site in the afternoon. When the hybrid model first began, it became clear very quickly that some students were not motivated to come to the site or to log in in the afternoon at all. ECV responded by providing an afternoon meal in order to incentivize students’ return to the center and online learning. The parents reported that this, in addition to an in-person adult who was regularly invested in their educational progress, reminding them when to log in and which assignments they needed to complete, boosted student feelings of support and consistency during an otherwise tumultuous part of the year.

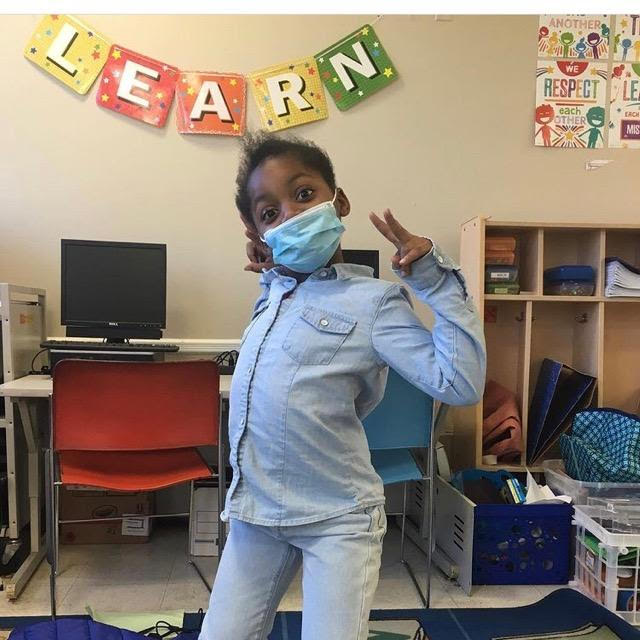

Parents were glowing in their description of ECV program offerings during 2020-2021, citing the reliability of operations and swift, clear communication as highest among the aspects of the programs that made their lives simpler and easier during the pandemic. One mother described the stress of evolving school schedules which was further exacerbated by the inconsistent closings of other outside programs, ultimately saying, “I can’t imagine life without ECV.” Because it was offered for a limited window in the morning, parents indicated that the BP and morning login time in particular served as an important source of structure and of motivation for their children to get out of bed, get dressed, and be somewhere. Leaving the house to go see ECV staff and coaches in-person helped students to maintain a sense of routine and experience some feeling of normalcy.

Coaches and parents reported that ECV responsiveness and flexibility, as well as their commitment to safe, in-person services, were critical to maintaining student engagement with the school system, with learning, and with a community of support in their own neighborhood. Parents interviewed noted that it was particularly beneficial for families with only one parent, who benefitted from local, proactive partners monitoring their child’s education. Even the parents whose children did not take advantage of the in-person services highlighted their gratitude for ECV’s efforts in this area. They indicated that this level of engagement from an outside entity sent a clear message that the community was important and valued. The parents interviewed felt that it both empowered individual students to stay in touch with school and insulated the neighborhood from experiencing a total breakdown during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. One coach echoed this sentiment, saying, “ECV had their doors open and had the kids at the center when everyone else was closed. I get emotional just talking about it.”

For the last several years, ECV has staffed a parent liaison who actively seeks to foster relationships with and create additional avenues of care for families in Eggerts Crossing Village. These efforts were supplemented in the 2020-2021 school year by the more widespread attempts of ECV staff and coaches to stay connected to students and their families. Staff texted parents and guardians when students were not in attendance either at ECV programs or at school. The latter updates were made possible by close collaboration with LTPS teachers, an element that is discussed later in this report. Coaches went out of their way to communicate individual student progress updates to families, letting them know of improvements, where more growth was needed, and how families could support the students given the school model implemented at any given time throughout that year. They reported that their relationships with many families improved and became closer that year as a result of the numerous adaptations – and subsequent communications -- that took place. The strength of the relationships was made evident by family and student actions. One family brought a coach a bouquet of flowers, balloons, and a meal in gratitude for her support through a particularly challenging week. In another instance, a coach and his family were invited to a student’s birthday party.

Consistent and personal communication between the families and ECV staff and coaches not only fostered genuine connections, they also created opportunities to meet additional family needs. All of the interviewed parents described how they received phone calls and masked, socially-distant home visits where ECV staff “really reached out to make sure everything was okay and to explain program details” and “checked-in to see what support we needed and how the kids were doing.” These conversations opened doors for ECV to provide wraparound supports for basic needs such as grocery store gift certificates, platters of food, and someone to walk students home from the ASP program or the bus stop. Because of their status as a long-standing, neighborhood-based program, ECV was uniquely positioned to meet basic family needs and thereby to provide a clearer path to educational enrichment during a time when barriers were pervasive.

Beyond COVID-19 pandemic specific circumstances, parents also communicated the importance of the longstanding bonds between ECV staff and coaches and their children, indicating that they feel “understood and known” and “part of a family.” One parent stated that her son has good memories of the program during the 2020-2021 school year, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, because of two staff members with whom he was close. Another was grateful that the staff “served as counselors and friends … mentors and big sisters” who were intentional about creating extracurricular space for the students to hang out and decompress from life. Due to their close relational and physical proximity to students, ECV staff filled a vibrant and mature social void in the lives of older students who were tired of being around their parents but who also were disconnected from many of their friends. Finally, two parents underscored the facilitating role that ECV staff/student relationships play in their children’s academic engagement, saying their children were “comfortable asking for help ECV but not at school” and “not very participatory in the classroom but very much so at ECV.”

Coaches noted that strong connections were not made with all families. While some families were highly engaged and took advantage of all the increased resources and services that ECV provided, others were, as one coach put it “just trying to get through each day.” They expressed frustration and disappointment with knowing about students who could have benefitted from the additional academic and social support, but whose families either did not enroll them in ECV programs or who took them home from the programs early. They indicated that these were the students who needed the most assistance and that the parents and guardians didn’t understand the value that extra enrichment would bring to their children. This is an area where ECV will continue efforts to promote the variety of programs offered and to educate families on their importance and benefit.

Remarkable Student/Teacher Ratio

Though the number of students served on any given day at ECV in the year 2020-2021 was lower than previous years due to COVID-19 pandemic factors such as intermittent quarantining, student or family illness, and social-distancing space limitations, the number of staff remained the same. This improved the already strong student/teacher ratios, particularly in the ASP. One coach reported that this advantage provided increased opportunities for 1:1 or 1:2 sessions with students who badly needed the additional support. In addition, recent (2021-2022 school year) changes to the ASP format facilitate longer stretches of academic enrichment time as well as dedicated time for coaches to work individually with students.

The story of one student who was repeating a grade was particularly illustrative of the benefits of this aspect of the program. His first year in the grade went poorly, and he was repeating the grade during the 2020-2021 school year where instruction was primarily on Zoom. He consistently exhibited anger-based behavior issues that inhibited his learning and his communication generally. However, once he began to receive 1:1, face-to-face instruction at the ASP, the coach described his progress as “a complete 180,” and he ultimately completed the grade successfully.

Another parent provided the example of her child who had transferred to LTPS not long before the COVID-19 pandemic and who struggled greatly with reading in both language arts and math contexts. The challenges of this situation were further exacerbated by the effects of remote learning. The child felt very insecure in an academic environment and rarely would speak or indicate when she needed assistance. However, the individual attention that she received at the BP and ASP created a supportive environment that kept her on a path forward. The parent described her joy when, “I would sneak over and watch them, and they were always engaged 1:1 with my child.” ECV staff and coaches gave her child “custom support and good directions” for how to complete her projects and assignments. Consistent attention at this level over time created a strong comfort level so that the child eventually felt safe asking for help and bringing up the places where she struggled. Her parent cited ECV – and the targeted instruction they provide -- as the resource she relies on most to help her “get her children where they need to be” in school.

Built-in SEL Component

One of the longstanding strengths of the ECV program that became particularly instrumental in the 2020-2021 school year was the built-in approach to SEL. Academic enrichment at the ASP is not fostered through rote pedagogical practices, but instead leverages the engaging power of games, story-telling, and peer interaction to reinforce the concepts that students learn in the classroom. One of the coaches brings to ECV the LTPS practice of using the Responsive Classroom approach in grades K-8. Responsive Classroom creates an environment that is developmentally responsive to student strengths and needs. Students practice self-awareness and relationship skills by learning to express themselves, to communicate effectively, and to develop positive relationships. This is one of the key ways that this coach achieves his goal for “learning at the ASP to be fun and meaningful.”

Just as important, the overarching structure of the ASP was described as one in which coaches “were able to impart to students, face-to-face, that they care.” For one of the coaches, the face-to-face nature of the ASP during some portions of the year was critical to achieving positive learning outcomes. She described the challenge of teaching younger students who were frustrated by new concepts to the point of tears on Zoom and the relief of being able to reassure those who were also in the ASP by saying “don’t worry about it, I’ll see you this afternoon at ECV.” Once in-person, she was able to bridge the virtual gap for these students by helping them to understand what they were missing and therefore to build confidence in their ability to learn.

SEL elements of instruction were further supplemented by BP staff members’ long-term relationships with the students and families in the Eggerts Crossing Village community. This meant that when students arrived in the morning, they were welcomed by a familiar and trusted face. Staff were intentional about making students feel valued by inquiring about their loved ones on a personal basis. One coach indicated that the strength of these relationships was “powerful to witness” and “helped get students in the door.”

Overall, by affirming and fostering close listening, confident speaking, growth mindset, and a community of caring, ECV coaches and staff supported LTPS in providing holistic student learning and support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another strength of the ECV programs that became particularly salient during the 2020-2021 school year was the fact that they are situated directly in the neighborhood where many of the students they serve live. Not only does this make program offerings highly accessible, but it poises ECV to foster family engagement generally and with LTPS events and services in particular. ECV staff and coaches were able to stop at student’s homes to check-in on them and see how they were doing. On a few occasions, the relationships developed between ECV coaches and staff and other LTPS teachers provided opportunities for the LTPS teachers to also stop at student homes. Some LTPS teachers even visited the Center to meet their students in-person, particularly ones that were struggling with remote learning. One coach remarked that it was “eye-opening” for her fellow LTPS teachers to visit Eggerts Crossing Village, to see where their students lived, and to get a sense of their home environments. In addition to check-ins, ECV staff and coaches also helped some families set up internet connections using the WiFi hotspot connections offered through LTPS. Parents cited this effort, and the subsequent in-home computer troubleshooting support that accompanied it, as an important factor in maintaining their children’s connection to their school classrooms.

ECV helped to facilitate other LTPS offerings as well. For example, an LTPS coach hosted a back-to-school night event at the ECV center in order to make it easier for parents to connect to their children’s teachers. She reported that, for those parents who attended, the ability to do so in their own neighborhood made a big difference. In another instance, ECV leadership and staff worked with LTPS to set up in-person evaluations at the K-3 center for students who were in the process of receiving an Individual Education Program classification when school buildings were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A speech pathologist, a psychiatrist, and other related professionals conducted their testing in spaces immediately adjacent to student’s homes, resulting in reduced time-to-classification and increased comfort and convenience to families in what is already a delicate process under the best of circumstances.

Coaches discussed at length the flexibility that LTPS provided to them in their role at ECV during the 2020-2021 school year. One indicated that the principal at her school released her from her normal responsibilities between 8:30 and 11:30 a.m. for a portion of the school year. This allowed her to be present with students at ECV who needed assistance logging in to their classroom or someone to help ensure that they were on the bus on time. This shift allowed her to function as a liaison between what was happening in the classroom and at ECV. At a later point in the year, when the ASP was able to offer in-person programming, she also returned to ECV in the afternoons. This meant that she started and ended her day in-person with some of the students who needed face-to-face time the most. In some cases, students who were in her online school classroom also attended her in-person ASP class, providing an important avenue for the reinforcement of hard-won academic concepts. In her words, this was a “gamechanger” for these students and would not have been possible without the support of LTPS leadership.

Another example of close ECV and LTPS collaboration was the relationships developed across the classroom teachers, the ECV staff, and the ECV coaches. These individuals exchanged phone numbers so that classroom teachers could communicate to ECV staff and coaches information that might otherwise fall through the cracks, such as when students weren’t online and what homework assignments were given. This was particularly beneficial for classroom teachers who wanted to request targeted, in-person support for ECV students in their class(es) and had limited avenues to provide it themselves or to obtain it through another source. This level of communication made it possible for ECV staff and coaches to respond to individual student circumstances in a way that was faster, more informed, and more precise than they typically would be able to execute.

This collaboration did not go unnoticed. The interviewed parents consistently described ECV relationships and close communication with LTPS as one of the most valuable components of the programming. They mentioned two distinct kinds of support that manifested from these relationships. The first, echoing ECV coach feedback, was the help students received in tracking and submitting assignments for their virtual classrooms. During a time when students were inundated by pandemic-related obstacles , the parents reported that this extra connection point was critical to keeping them on track and feeling successful.

The parents also highlighted ECV’s model of supporting their children’s classroom teachers by bridging specific learning gaps. For example, one mother said, “They communicate with his school when [my son] has issues with math. He scored low on his last test, so I asked his teacher to communicate with [ECV] about getting targeted help. It’s like a safety net.” Another stated that the connection with teachers is “huge” and was especially helpful as her child approached the transition to the complexities of middle school. For parents who were single, this added level of support relieved some of the pressure of juggling their children’s day-to-day academic struggles with other parental stressors such as work, transportation, and financial challenges. Although the connection to LTPS was particularly appreciated during the COVID-19 pandemic, parents noted that it was built into the ASP design well before that. One stated, “Our kids have had a great experience with Lawrence because of ECV.”

In addition to the specific stressors described in the previous section, the COVID-19 pandemic also took a general toll on ECV coaches, staff, and students resulting from a high degree of stress and unpredictability on a daily basis. The year and its challenges were deeply wearing for all involved. Nevertheless, coaches commented that it fostered out of necessity many important relationships and innovations that they hoped would continue in some form.

Foremost of these were the close and fluid relationships between ECV staff and LTPS staff. The coaches reported that their frequent communication with LTPS classroom teachers, described in detail earlier in this report, fostered better and more customized academic and social and emotional support for students in ECV programs increased the quality of ECV program/LTPS interactions, and facilitated connections between ECV families and LTPS. ECV coaches underscored the value of these outcomes to a wide stakeholder list and indicated a desire to see them continue.

An important outgrowth of closer ECV staff/LTPS relationships was the manifestation of additional intersection points for collaboration. Temporarily transitioning the Individual Education Program classification process to local contexts such as the ECV neighborhood is one such example. Coaches reported that the families who participated in this process were more at ease engaging in testing and test-related conversations in familiar and comfortable spaces. This arrangement also eliminated the need for families to coordinate transportation to testing appointments, eliminating a seemingly small but often impactful hurdle to access LTPS services. ECV coaches questioned why this straightforward and beneficial adaptation would have to end after the 2020-2021 school year. They also indicated that the continued 1) encouragement and opportunity for LTPS staff to visit Eggerts Crossing Village and 2) offering of a Zoom option for school events would facilitate stronger ECV family and LTPS relationships and engagement in a post-COVID era.

Finally, ECV coaches noted that there was a decrease in enrollment at the ECV ASP when a cost for this programming (which was temporarily suspended for a portion of the school year) was re-introduced. They questioned whether there was a way to continue to provide a 100% subsidy to those ECV families impacted by a financial obstacle of any size. This is a challenge that ECV leadership will continue to explore. The fees associated with the ASP are low, and ECV provides access to – and support in completing the requirements for - financial aid resources for families who need it. Nevertheless, it appears that either the cost itself, the time investment needed to obtain financial assistance, or both, remain a hurdle for some families.

While the 2020-2021 school year brought significant individual and systemic barriers to student attendance and engagement, the ECV coaches and a sample of parents delivered vivid illustrations of the ways in which ECV programming and staff pivoted to support the LTPS efforts to address them. While those efforts were substantial, the ECV programs and services were a critical supplement developed to target the particular needs of a low-income subgroup of students within the district. Certainly, the introduction of the Learning Pod was foremost among these programs, providing a safe and supportive space for students to engage with their online classrooms and to receive individualized instruction and support. Parents and coaches alike indicated that close ECV staff and family relationships, facilitated by the proximity of programming to student homes, served as natural connection points for ECV staff to deliver both practical and SEL-related support. Timely and accommodating support from LTPS leadership and teachers allowed ECV to expand the breadth and impact of their services to include twice-daily academic enrichment from the ECV coaches, rapid follow-up with students who were absent or delinquent in their assignments, and instruction customized to areas where students needed it most. While no set of measures could be far-reaching enough to completely mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, those put in place by ECV were critical to reducing the impact to some of the most vulnerable residents in Lawrence Township.

References

Aguiliera, E., and Nightengale-Lee, B. (2020), Emergency remote teaching across urban and rural contexts: perspectives on educational equity. Information and Learning Sciences, 121, 471-478. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0100

Catalano, A. J., Torf, B., & Anderson, K. S. (2021). Transitioning to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences in access and participation among students in disadvantaged school districts. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 38, 258-270. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-06-2020-0111

Halloran, C., Jack, R., Okun, J. C., & Oster, E. (2021). Pandemic schooling mode and student test scores: Evidence from US states (No. w29497). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29497/w29497.pdf

Kanopka, K. Claro, S. Loeb, S., West, M., & Fricke, H. (2020). What do changes in social-emotional learning tell us about changes in academic and behavioral outcomes? [Policy brief]. Policy analysis for California education. https://edpolicyincas.org/publications/changes-social-emotional-learning

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., & Lewis, K. (2022). Test score patterns across three COVID-19-impacted school years. Annenberg Institute Working Paper, 22-521. https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai22-521.pdf

Lewis, K., Kuhfeld, M., Ruzek, E., & McEachin, A. (2021). Learning during COVID-19: Reading and math achievement in the 2020-21 school year. Center for School and Student Progress. https://www.nwea.org/research/publication/learning-duringcovid-19-reading-and-math-achievement-in-the-2020-2021-school-year

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). (2021, March 21). Persons in low-income households have less access to the internet. ASPE Reports. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/low-income-internet-access

Santibañez, L., & Guarino, C. M. (2021). The effects of absenteeism on academic and social-emotional outcomes: Lessons for COVID-19. Educational Researcher, 50, 392-400. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X21994488

Yaya, S., Yeboah, H., Charles, C. H., Otu, A., Labonte, R. (2020). Ethnic and racial disparities in COVID-19-related deaths: Counting the trees, hiding the forest. BMJ Global Health, 5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002913

|